Note: due to the large images in this page, you might wish to view it in a separate window. Click here to do so.

The telegraph line between Washington and Baltimore started off as a pipeline. Wires put in pipes were protected from wind and weather. It was a good idea, but the wire had bad insulation and didn't work. Up against a deadline to get the city-to-city line completed, the construction engineer, Ezra Cornell, had to order good wire. He realized he was running out of time. So he had a new idea: the quickest and cheapest way of doing the job was to string the good new wire on trees and poles. Morse approved, and Cornell got the line finished in time. The historic message "What Hath God Wrought?" ran on wires running from the Supreme Court chamber of the Capitol building to a railroad station in Baltimore. Soon there were wires on poles all over the country. We still see them today. Next time snow or ice or winds knocks one down near you, think of what a good idea the pipe was.

The telegraph caught on fast. One of the first companies to make money with the telegraph was the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company, founded in 1851. Five years later, the company changed its name to Western Union. The word "Western" in its name reminded people that the telegraph was heading in that direction, but it still had a long way to go. Until Western Union completed the first telegraph line across North America in 1861, anyone wanting to send a message beyond Missouri had to use the Pony Express. To many Americans, the idea of instant, long-distance communication was still something close to miraculous -- thought not often of practical use. Most people had no need to know what was happening three thousand miles away three minutes after it happened.. But railroads knew the telegraph's value. They needed the fastest possible communcation between stations in order to keep the trains running, and running telegraph cable alongside a rail line became standard procedure in short order. Soon wherever there was a railroad line there was a telegraph line. And once the lines were there, it made all the sense in the world to make use of them to send and receive non-railroad messages.

Just as Lincoln made of speedy train travel to shore up his political support as he arrived in Washington (see notes on Chapter One), Confederate President Jefferson Davis also made use of the railroad to get his message across. Between December 10, 1862 and January 5, 1863, he made a long and difficult journey the length and breadth of the Confederacy rallying the people and the troops to fight on.. He traveled to Lynchburg. Knoxville, Chattanooga, Atlanta, Montgomery, Jackson, Vickburg, Grenada, Mobile, back through Montgomery and Atlanta, then on to Columbia, Charlotte, Greensboro, Raleigh, Wilmington, Goldsboro, and finally back to Richmond. He traveled more than 2500 miles and made 25 public addresses in 25 days, as well as meeting with many of his most important military commanders,

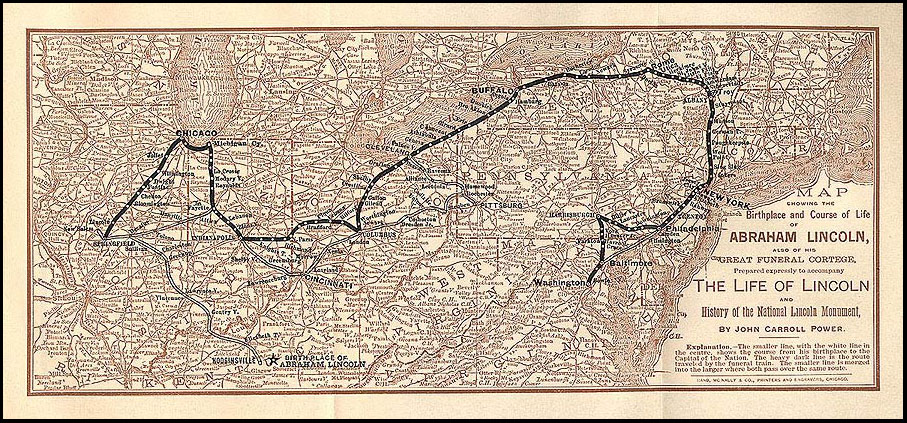

After his assassination, Lincoln traveled home on the train as well, in a special train that covered thousands of miles, stopping and passing through hundreds of towns and citys.

Click on the image of the map below to be taken to a website run by the The Lincoln Highway National Museum & Archives detailing the journey.

At the end of the war, Jefferson Davis likewise departed his capital city on a train -- but under vastly different circumstances -- circumstances closer to farce than tragedy. As Richmond fell, Davis and the entire Confederate Government -- or what was left of it -- boarded a train , and headed toward Danville, Virginia, which became the de-facto capital of the Confederacy from April 3 to 10, 1865. They followed behind a "treasure train" loaded with papers, gold, and other valuables. Davis hoped at first to join up with Confederate forces still in the field in North Carolina. Failing that, he would try to get across the Mississippi and continue the struggle from Texas. But Union forces seemed to be everywhere, and his party dared not stay in one place too long. They continued on, at first in railcars, and then on horseback. Government officials and members of the cabinet -- the Attorney General for a nation that had no court system, the postmaster whose department could no longer deliver the mail, the Secretary of a a Navy that no longer existed -- found reasons to depart, one by one. Davis himself was finally captured on May 10, 1865 near Irwinville in southern Georgia.