|

|

|

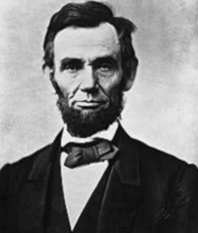

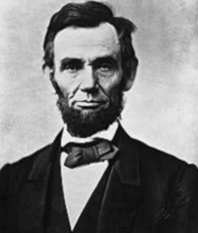

Abraham Lincoln

|

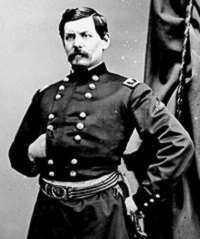

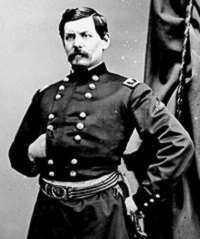

George B. McClellan

|

Lincoln's latest reorganization did not last long. The Confederates defeated Pope soundly at the Second Battle of Manassas. His army's effectiveness and morale were so badly damaged that Lincoln was forced to appoint McClellan to command all the troops around Washington. Lincoln was most reluctant to bring McClellan back, but, as he told his secretary, "[w]e must use what tools we have. There is no man in the army who can ... lick these troops of ours into shape.... If he can't fight himself, he excels in making others ready to fight.".

McClellan believed in what might be called "soft war," fought in an almost gentlemanly way between armies, leaving civilian life and "existing institutions" (a polite phrase politicians often used when they meant slavery) undisturbed. McClellan wrote to Lincoln saying "[n]either confiscation of property ... or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment."

But his own actions did a lot to discredit soft war. If, during the Peninsular Campaign, McClellan had understood how small the Confederate force before him was, and if he had taken some risks, he very likely could have captured Richmond, scattered the rebel armies, and shortened the war. It was his excessive caution and fear of imaginary giant Confederate armies that allowed him to be fooled and chased off. That insured the war would be much longer, and much harder. The extension and expansion of the war drove Lincoln to strike against slavery as a matter of military necessity. The war would turn it from the gentleman's contest McClellan sought into the long, hard, no-holds-barred four-year struggle it became. Thus, it could be argued that it was the failure of McClellan's soft-war schemes that forced Lincoln toward a hard-war policy that would doom slavery.

Lincoln fought the Civil War not to end slavery, but to save the Union. He hated slavery, and wanted it to end. But he had to contend with many pro-Union politicians who were also pro-slavery. Slavery was still legal in four Union states -- Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky and Missouri. On August 22, 1862, Lincoln wrote to newspaper publisher Horace Greeley: "My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that."

Lincoln did not decide to impose "forcible abolition" -- by issuing the Emancipation Proclamation -- until after McClellan's defeat in the Peninsular Campaign and other military failures that he felt left him with no other choice. Taking the advice of his secretary of state, Lincoln decided not to release the Proclamation until after a Union victory.

McClellan started the campaign that led to the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) with a huge intelligence advantage over his enemy: a copy of Lee's battle plans came into his hands. McClellan was jubilant. "Here is a paper," he said, "with which if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home." He did not beat Lee. Soon after, he did go home -- but not willingly. He frittered the advantage of the battle plan intelligence away in caution and doubt, once again believing the enemy forces were larger than they were. McClellan fought the Confederates to a standstill at Antietam in mid-September. Many historians believed he mis-handled his troops that day, sending them on piecemeal attacks that were not large enough to succeed. He then failed to pursue the retreating rebels after the fight. Lincoln visited McClellan near the battlefield some time later. Looking down on the army camp, he told a friend that the vast display of men and equipment down below was not the Army of the Potomac. "No..." he said. "This is General McClellan's body-guard."

But that bitter joke almost got it backwards. McClellan's excessive caution wasn't caused by the army protecting their general. It was the general protecting the army, unwilling to see his great creation harmed. It was observed more than once that McClellan loved the army as a father loved his sons. No father would willingly risk the lives of his sons. "Gen[eral] McClellan thinks he is going to whip the rebels by strategy[,]" Lincoln wrote to a friend, "and the army has got the same notion. They have no idea that the war is to be carried on and put through by hard, tough fighting that will hurt somebody, and no headway is going to be made while this delusion lasts...."

Antietam was hard fighting -- the bloodiest day in American history -- but it was not a clear-cut victory. It was, however, probably the closest thing to a victory that Lincoln would see for a while. He released the Emancipation Proclamation after the battle, and announced it would go into effect January 1, 1863. It freed all slaves in areas that were in rebellion, but did not affect slaves in the loyal states. It was a military measure that Lincoln made as commander-in-chief. It freed slaves in order to hurt the Confederacy. The southern economy relied on slavery to function. Every slave who stopped working helped to weaken the enemy. But the Proclamation did more. It changed the war to save the Union into something more -- a war to end slavery.

Lincoln waited until the fall elections were safely over before moving to fire the politically popular McClellan for the second time in November 1862. Lincoln appointed General Ambrose Burnside to head the Army of the Potomac. Burnside commanded the disastrous Union attack on Frederiksberg in mid-December, and then attempted to redeem himself with another attempt on January 20, 1863. About all he accomplished was to prove was that it was in fact very risky and difficult to conduct operations in mid-winter weather.

The Union forces started out in fine weather -- but then it started to rain. And rain. The army struggled for two days to move through the knee-deep mud churned up by its marching before Burnside abandoned the plan. The ordeal was so severe that the operation became known even in official records as "The Mud March." On January 26, 1863, Lincoln gave up on Burnside, and appointed Major General Joseph Hooker in his place. But Hooker was to create his own disaster, at the Battle of Chancellorsville.