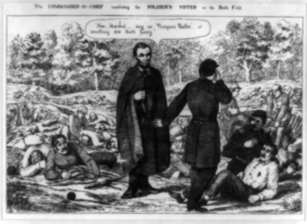

The Commander-in-Chief Conciliating the Soldiers Votes

Click on the cartoon for a larger view of a higher-quality view of the image. Lincoln is seen wearing a cloak and scotch cap, a visual reference to the false story that he wore those items while sneaking through Baltimore. The cap and cloak became a frequently-used cartoonist's shorthand for suggesting to the readers that Lincoln was cowardly. Here, he is shown as coming to the battlefield after the fighting is over, and asking his friend to sing him a funny song in the midst of a scene of horrible suffering. Lincoln, in other words, fears for his own safety but cares nothing for his troops. Click on the cartoon for a larger view of a higher-quality view of the image. Lincoln is seen wearing a cloak and scotch cap, a visual reference to the false story that he wore those items while sneaking through Baltimore. The cap and cloak became a frequently-used cartoonist's shorthand for suggesting to the readers that Lincoln was cowardly. Here, he is shown as coming to the battlefield after the fighting is over, and asking his friend to sing him a funny song in the midst of a scene of horrible suffering. Lincoln, in other words, fears for his own safety but cares nothing for his troops.

From the Library of Congress description of the image:

A bitterly anti-Lincoln cartoon, based on slanderous newspaper reports of the President's callous disregard of the misery of Union troops at the front. The story that Lincoln had joked on the field at Antietam appeared in the "New York World." Holding a plaid Scotch cap ... Lincoln stands on the battlefield at Antietam, which is littered with Union dead and wounded. He instructs his friend Marshal Lamon, who stands with his back toward the viewer and his hand over his face, to "sing us Picayune Butler,' or something else that's funny."

As related in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, the background of this grim cartoon is as follows: Ward Lamont, a close friend of the President, received the following letter:

"[To] Ward H. Lamon: Philadelphia, Sept. 10, 1864.

"Dear Sir,---Enclosed is an extract from the New York `World' of Sept. 9, 1864:---

"'ONE of MR. LINCOLN'S JOKES.---The second verse of our campaign song published on this page was probably suggested by an incident which occurred on the battle-field of Antietam a few days after the fight. While the President was driving over the field in an ambulance, accompanied by Marshal Lamon, General McClellan, and another officer, heavy details of men were engaged in the task of burying the dead. The ambulance had just reached the neighborhood of the old stone bridge, where the dead were piled highest, when Mr. Lincoln, suddenly slapping Marshal Lamon on the knee, exclaimed: "Come, Lamon, give us that song about Picayune Butler; McClellan has never heard it,'' "Not now, if you please," said General McClellan, with a shudder; "I would prefer to hear it some other place and time.'"

"This story has been repeated in the New York 'World' almost daily for the last three months. Until now it would have been useless to demand its authority. By this article it limits the inquiry to three persons as its authority,---Marshal Lamon, another officer, and General McClellan. That it is a damaging story, if believed, cannot be disputed. That it is believed by some, or that they pretend to believe it, is evident by the accompanying verse from the doggerel, in which allusion is made to it:---

'Abe may crack his jolly jokes

O'er bloody fields of stricken battle,

While yet the ebbing life-tide smokes

From men that die like butchered cattle;

He, ere yet the guns grow cold,

To pimps and pets may crack his stories,' etc.

"I wish to ask you, sir, in behalf of others as well as myself, whether any such occurrence took place; or if it did not take place, please to state who that 'other officer' was, if there was any such, in the ambulance in which the President `was driving over the field [of Antietam] whilst details of men were engaged in the task of burying the dead.' You will confer a great favor by an immediate reply.

"Most respectfully your obedient servant,

"A. J. PERKINS."

[Civil War ambulances were basically horse-drawn carriages. It was an accepted practure for them to be used to carry officials and high-ranking officers around forward areas.]

Lamont apparently brought this letter, or at least the news of this story, to Lincoln's attention. Lincoln took the charge seriously enough that he then drafted the following letter himself, which was to go out over Lamont's signature. To quote from the account in the Collected Works: "According to Lamon (Recollections of Lincoln, pp. 144-49), Lincoln wrote this memorandum `about the 12th of September, 1864,' to be published, if necessary, in refutation of a story widely disseminated by the Copperhead press. The memorandum was not, however, given to the newspapers." The text of the memorandum was as follows:

The President has known me intimately for nearly twenty years, and has often heard me sing little ditties. The battle of Antietam was fought on the 17th. day of September 1862. On the first day of October, just two weeks after the battle, the President, with some others including myself, started from Washington to visit the Army, reaching Harper's Ferry at noon of that day. In a short while Gen. McClellan came from his Head Quarters near the battle ground, joined the President, and with him, reviewed, the troops at Bolivar Heights that afternoon; and, at night, returned to his Head Quarters, leaving the President at Harper's Ferry. On the morning of the second, the President, with Gen. Sumner, reviewedPage 549 the troops respectively at Loudon Heights and Maryland Heights, and at about noon, started to Gen. McClellan's Head Quarters, reaching there only in time to see very little before night. On the morning of the third all started on a review of the three corps, and the Cavalry, in the vicinity of the Antietam battle ground. After getting through with Gen. Burnsides Corps, at the suggestion of Gen. McClellan, he and the President left their horses to be led, and went into an ambulance or ambulances to go to Gen. Fitz John Porter's Corps, which was two or three miles distant. I am not sure whether the President and Gen. Mc. were in the same ambulance, or in different ones; but myself and some others were in the same with the President. On the way, and on no part of the battleground, and on what suggestion I do not remember, the President asked me to sing the little sad song, that follows, which he had often heard me sing, and had always seemed to like very much. I sang them. After it was over, some one of the party, (I do not think it was the President) asked me to sing something else; and I sang two or three little comic things of which Picayune Butler was one. Porter's Corps was reached and reviewed; then the battle ground was passed over, and the most noted parts examined; then, in succession the Cavalry, and Franklin's Corps were reviewed, and the President and party returned to Gen. McClellan's Head Quarters at the end of a very hard, hot, and dusty day's work. Next day, the 4th. the President and Gen. Mc. visited such of the wounded as still remained in the vicinity, including the now lamented Gen. Richardson; then proceed[ed] to and examined the South-Mountain battle ground, at which point they parted, Gen. McClellan returning to his Camp, and the President returning to Washington, seeing, on the way, Gen Hartsuff, who lay wounded at Frederick Town. This is the whole story of the singing and it's surroundings. Neither Gen. McClellan or any one else made any objection to the singing; the place was not on the battle field, the time was sixteen days after the battle, no dead body was seen during the whole time the president was absent from Washington, nor even a grave that had not been rained on since it was made.

WARD H LAMON

|