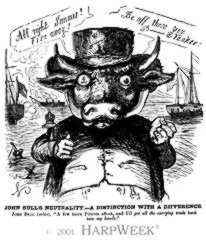

Click on the above image for a larger view of this Northern cartoon. The British Bull (a pun on "John Bull, the British equivalent of "Uncle Sam) seems to have more of an eye for money than neutrality.

Click on the above image for a larger view of this Northern cartoon. The British Bull (a pun on "John Bull, the British equivalent of "Uncle Sam) seems to have more of an eye for money than neutrality. (Note: this text includes an expanded account of some events described in the book itself, along with other material.)

At the very start of the war, the British government laid down certain rules: it would allow the Confederacy to buy ships -- so long as they weren't warships. The game, so far as the James Bulloch and other Confederate ship agents in the United Kingdom were concerned, would be to obtain ships that weren't equipped for war, but that could be. The Confederates would then arrange for these "civilian" ships to leave British waters and then put them together with the guns, ammunition, crews and officers that would turn them into fighting ships.

The Confederates and their allies would have to do this while U.S. Minister [the term used for "ambassador" at the time] Charles Francis Adam and his alert Union diplomats and spies used every means at hand to stop them. Chief among these diplomats was Thomas Dudley, the U.S. general consul. [A consulate is basically a branch office of an embassy, usually placed in a city where there is a lot of business being done between the two countries. A consul is the manager of the embassy's branch office.]

Despite all the obstacles, Bulloch managed to get construction started on the first Confederate cruiser before the month of June 1861 was out -- with all parties to the deal pretending as hard as they could that she was not a warship to be named the C.S.S. Florida, but merely an innocent commercial vessel named "Oreto." No one felt the need to point out that her design was based on plans for a Royal Navy ship built to carry big guns. Once the Florida-to-be's construction was well underway, Bulloch made arrangements with another shipyard to built a vessel referred to only as hull No. 290. But she was in fact to be the C.S.S. Alabama.

Bulloch proudly declared No. 290 "equal to any of her Majesty's ships of corresponding class in structure and finish, and superior to any vessel of her date in fitness for the purposes of a sea rover, with no home but the sea, and no reliable source of supply but the prizes she might make."

By March 1862 No. 290 was ready to launch -- but U.S. Minister Adams was doing whatever he could to get the British government to prevent her from leaving port. The ship -- at that point using the cover name "Enrica" -- still had to undergo engine trials and other preparations that gave Adams more time to stop her. The Union diplomats filed a former request for her seizure on July 26. The British finally agreed on the 29th. But the "Enrica" had already sailed.

Three weeks later the Alabama,by then sailing under her proper name, rendezvoused with auxiliary ships in a bay on the island of Terceira in the Azores, in mid-Atlantic. The other ships carried her guns and equipment and her crew. Finished with subterfuge, Captain Raphael Semmes put on his Confederate Navy uniform, sailed into international waters, and raised the Confederate naval ensign above the C.S.S. Alabama for the first time on August 24, 1862. His ship sailed the oceans of the world for the next twenty-one months, acheter cialis 20mg, attacking whatever U.S. merchant vessels he could find. She took over sixty prizes [captured ships].

The threat posed by the Alabama forced ship owners to delay sailings, to pay more for insurance, and to change their ship's registry to that of other countries. She caused an uproar in the U.S. merchant fleet, and the U.S. Navy was forced to send ships in pursuit of her and the other raiders. She sailed in the Gulf of Mexico and approached the Texas coast -- where she attacked and sunk the U.S.S. Hatteras. -- but the Alabama never touched the shore of North America..

She cruised the North and South Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean. After remaining almost continuously at sea for the better part of two years, the Alabama was in need of repairs and refits. She put into port at Cherbourg, France on June 11, 1864. But the U.S.S. Kearsarge was standing off the Dutch coast, keeping watch on another Confederate ship that was in dry-dock. The U.S. consul at Cherbourg alerted the U.S. ambassador to France, who in turn contacted the captain of the Kearsarge, John A. Winslow. She immediately sailed for Cherbourg, arriving on the fourteenth. The Alabama had attacked scores of ships, but only once before had she fought another armed vessel -- and the Hatteras had been no match for her at all. The Alabama's victory over the Hatteras was only time that a Confederate ship defeated a Federal ship on the high seas. It was time to see if she could do it again. On Sunday, June 19, 1864, a crowd gathered on the docks and on the shore, and on boats at sea to watch the battle. All of the advantages were with the Kearsarge, and a little more than an hour later, the Alabama was sinking, with massive holes in her side. She surrendered and requested assistance with her wounded. Winslow, wary of Semmes playing one last trick, moved cautiously. He allowed Semmes and many of her crew to be rescued by the private British yacht Deerhound (though some accounts say Semmes escaped, rather than being let go -- see discussion below). Semmes eventually made his way back to the Confederacy.

The noted impressionist painter Édouard Manet created two canvases, one of the battle itself, and one of the victorious Kearsarge at anchor. Through the vicissitudes of maritime law, the wreck itself is now the property of the U.S. government. A French-American team conducted archeological recovery work. More information on the dive operations, and the ship itself, is available at www.css-alabama.com/. See also this U.S. Navy web page: http://www.history.navy.mil/research/underwater-archaeology/sites-and-projects/ship-wrecksites/css-alabama/css-alabama-lost-and-found.html.

As we were writing Mr. Lincoln's High-Tech War, we discovered that digging through the accounts of what did or did not happen at the end of the battle on June 19, 1864 was an adventure in contradictions. A History of the Confederate States Navy, 1996, Raimondo Luraghi, page 319, says the Deerhound helped in the rescue "at Winslow's request." One page of photos at a "mirror" site that displays the former contents of the photo collection at the Naval History and Heritage Command, http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/sh-us-cs/csa-sh/csash-ag/alabama.htm merely says "her surviving crewmen were rescued by the victorious Federal warship and by the English yacht Deerhound." [See bibliographic notes for further discussion of these mirrored pages.] The Dictionary of American Fighting Ships at the same website says this in its entry for the Alabama: "Kearsarge rescued the majority of Alabama's survivors, but Semmes and 41 others were picked up by the British yacht Deerhound and escaped in her to England." The Kearsarge entry elaborates a bit more: "Semmes struck his colors and sent a boat to Kearsarge with a message of surrender and an appeal for help. Kearsarge rescued the majority of Alabama's survivors; but Semmes and 41 others were picked up by British yacht Deerhound and escaped in her to England." In Under Two Flags: The American Navy in the Civil War, William M. Fowler Jr says that the Kearsarge kept firing for a while after the Alabama signaled her surrender by lowering her flag. (As is reported in many sources, Semmes had played games with flags before, often raising the British flag or even the Union flag in order to get in close to a victim.) Fowler is silent as to whether Semmes was allowed to depart or if he escaped, and just reports that he was "deposited on the docks at Southhampton." To Shining Sea, Stephen Howarth, 1991, page circa 207, says "[Semmes] struck his colors in surrender, but Kearsarge, thinking the flag had only been shot away, fired five more times, stopping when the Confederate began to settle in the water and and men were seen jumping overboard." Howarth is likewise silent on the let go/escaped question. Foote, in Volume II page 380-390 of The Civil War: A Narrative gives an extensive account, and reports Semmes ran down his colors, Winslow said "he's playing a trick on us" and ordered one more broadside, after which the Alabama ran up a white flag at the stern. Foote has Winslow use a speaking trumpet to hail the Deerhound and shout "For God's sake do what you can to save them!"

One other note of confusion: At least one source referred to the Deerhound as the Greyhound. There were no fewer than three ships named Greyhound at about that time -- one Union, one Confederate, and one British.